- Home

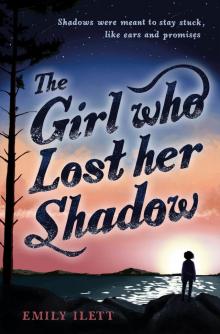

- Emily Ilett

The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow

The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow Read online

Contents

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter One

Gail was eating cornflakes when her shadow disappeared. She didn’t even really like cornflakes. It happened, she thought, between the third and fourth mouthful. She watched the shadow slip under the kitchen door, rippling like an eel into the garden, leaving Gail with an itch in her right foot and a dribble of milk on her chin. She wasn’t surprised. Everything was falling apart, including her. And it was all Kay’s fault.

Kay was Gail’s sister. She was three years, four months and seven days older than Gail. She had two seaweed-green stripes in her twisty hair, a gold hoop in her nose and teeth so crooked they looked like they’d been caught mid-somersault. She’d been the best swimmer on the island ever since she first learned backstroke. But now she was sinking.

Gail pressed her face to the window and saw her shadow flicker through the grass. It was the morning of her twelfth birthday and it felt nothing like it should. Her dad had left two months ago, her mum was headed to work and Kay was in bed. Like she always was, now.

“Take this up to your sister, Gail honey.” Her mum slid a plate of toast in front of her. “And don’t eat all the cake.”

Gail stared at the birthday cake. It looked like a cowpat. Brown icing dribbled in sticky globs onto the table. On the top, blue Smarties spelled out Gale. Spelling Gail ‘Gale’ was her dad’s old, unfunny joke. He’d told her that on the night she was born, her screams were so fierce she’d drowned out the wail of the gale-force winds spinning around the hospital. That’s why they’d named her Gail.

The fridge light blinked on and off as her mum rushed around the kitchen, checking that her sister’s favourite dishes were still stocking every single shelf. It had been like this for weeks. Gail scowled. It was her birthday; Kay should be bringing her breakfast. Gail flicked her spoon and watched as a drop of milk sailed onto Kay’s toast.

“Guess what, Mum? My shadow’s disappeared.”

“What’s that, honey?” Her mum glanced towards the ceiling as the toilet flushed upstairs.

“It went right under the door. I saw it in the garden.”

The wrinkles around her mum’s dark eyes trembled as she forced a smile. “Is that right, honey? That sounds interesting. You’ll tell me all about it later, won’t you?” She rooted in her handbag for the keys. “Remember Kay’s toast.”

Gail scratched the itch on her right foot harder.

“She won’t eat it.”

Her mum was already marching towards the door, her nurse’s uniform flapping like old pancakes behind her. “Kay loves Marmite,” she said. At the door, she turned. “Hey, Gail.” She paused. “Maybe Kay will want to swim today.”

Gail glared after her. Kay hated Marmite and she never wanted to swim any more. They used to swim every week, but everything had changed after their dad left. Now, Kay never left her room if she could help it. She hardly ate, and if she looked at Gail, it was like she was looking all the way through her, as if she was invisible.

Today, invisible was exactly how Gail felt.

Gail stood up, picked a Smartie out of the ‘a’ in Gale, crunched down hard and pulled the plate of toast closer. The house felt too small for everything that was happening inside. It was like the air was being squeezed out of it, making it harder and harder to breathe.

With the toast in one hand, Gail climbed the stairs. Kay was in her bedroom staring out of the window onto the grey cracked wall of the newsagent next door. Gail could see that Kay’s eyes were jellyfish-pink at the edges. She rubbed at them when Gail came in.

“Hey, happy birthday.” Kay’s voice was old and tired. “You’re not in school?”

Gail balanced the plate on the bed. “It’s Saturday.” Kay never knew what day it was. She hadn’t been to school since it started back after summer. She just slept all the time. The room stank of sleep. Kay’s bedside lamp cast slippery shapes on the walls, which were covered with shiny posters of squid, sea-dragons and whales.

Gail took a deep breath. “I’m going down to the beach.” She shrugged her shoulder towards the window. “Do you want to come? It’s been ages since we swam.”

Kay chewed her lower lip and Gail followed her gaze as her eyes shifted beyond the newsagent to the ocean, blue-grey and glittering beneath them.

It was Kay who’d first taught Gail to swim. Gail had swallowed chlorine in the town pool till she felt sick and dizzy, Kay’s hands holding up her stomach. Then, when she’d learned breaststroke, they’d clambered down to the pebbly scrap of beach below their house, where the ocean sucked at the stones like sweets. Even in summer, the water was so cold it burned. Lifted by waves, they’d swap stories of deep-sea explorers, and imagine turtles and spider crabs beneath the surface whenever their toes brushed against something in the water. They’d dare each other to swim further and further and faster and faster, and do handstands underwater with their eyes open and stinging. They’d collect cowrie shells and razor clams, and one time Gail had found a dead starfish which they’d dissected later in the bath.

Each time they swam, waves rolled over them and through them like a whale’s heartbeat, and they’d clutch each other’s hands and lick salt from their lips and dream of diving in the reefs of Barbados and all the sea creatures they were going to care for or discover when they became marine biologists. Because they were always going to swim together. Always.

Gail tore her gaze from the heaving sea and stared at her sister. The green twist of Kay’s hair hung limply against her face, and her eyes were flat and empty. It was as if a light inside her had gone out. “I want to go swimming, Kay. Come on, Mum says there’s a big storm coming and we’ll be stuck inside tomorrow.”

Kay blinked and shook her head as if coming out of a deep sleep. “Hey,” she said. “I forgot…” Reaching beneath the bed, she brought out a long tube. “Happy birthday, Sis.”

Gail winced ‒ Kay never called her Sis ‒ and pulled the poster out of the tube. The glossy paper unfurled to reveal a giant manta ray, its fins sweeping like wings through the water. Gail stared at it. Manta rays were Kay’s favourite sea creature. She must have bought the poster for herself a long time ago and forgotten about it. It wasn’t meant for Gail at all.

“Do you like it?”

Gail swallowed and nodded. “Yeah. Thanks.” Her hands tightened on the edges of the paper. “Are you coming swimming?”

Kay shook her head. “No. I don’t think so.”

Gail’s fingers squeezed the poster harder. “Come on, you always say that. It’s my birthday, Kay.”

Kay turned away. “I don’t want to.”

“But it’s my birthday!”

“I’m sorry, Gail. I can’t. I… You go.”

Blood rushed to Gail’s cheeks. She couldn’t go

alone. They both wanted to be marine biologists but Gail was terrified of drowning. She never swam by herself. Kay knew that. A hot, prickly anger pulsed through Gail. “You don’t want to do anything any more! All you do is sit here feeling sorry for yourself! Mum says you’re ill but you’re not really. You’re just selfish!” Gail began tearing at the poster, ripping the manta ray into smaller and smaller pieces. “What about me, Kay?”

“Gail—” Kay began, her mouth open in shock.

“It’s my birthday and I can’t swim by myself and you just stay here staring with your stupid, selfish…”

“Don’t…” Kay reached out to her but Gail wriggled away. Fragments of paper spilled onto Gail’s feet and when she looked down her toes were covered in dark grey slices of manta ray.

“And my shadow’s gone,” she burst out, pressing her hands to her sides to stop them shaking. “You’re meant to be the sick one, but yours is still here.”

She kicked her foot against the carpet where Kay’s light-grey shadow was poised, and a rush of something broken and hurting and heavy flooded her body, making her knees tremble. Gail staggered against the wall. Her feet prickled as Kay’s shadow gathered around them, silken between her toes. She gasped at the force of it. She felt emptied of everything she cared about, hollow like a clam shell cast up on a beach. She tried to swallow the lump that was blocking her throat and making her eyes burn. Was this how Kay felt?

Then, before Gail’s legs buckled completely, Kay’s shadow silently slid away from her towards the door, as if it had somewhere else to be. At the edge of the carpet it paused, hesitating for a second, but then the dark shape tightened, as if a decision had been made, and the shadow slipped out of the room.

Kay’s eyes widened as she stared at the empty places where their shadows should be. The floor looked embarrassed.

Gail held her breath.

“Get it back, Gail,” Kay said at last. Her voice shivered and the hoop in her nose shone dimly. “Get it back.”

Chapter Two

Rain tapped against the kitchen window as Gail stuffed sandwiches and gloves into her backpack. Next to the gloves she squeezed the red torch her mum had given her that morning, a birthday gift so Gail could watch the rock pools come alive with crabs after dark. Tucking her phone into the pocket of the bag, Gail pulled a face. She always took it with her, though there was never any signal on the island. Too many steep hills and valleys. On a corner of newspaper, its headlines warning of the next day’s storm, she scrawled:

Gone to Rin’s. Be back soon.

Rin was Gail’s friend. Or she used to be.

How long would it take to find Kay’s shadow? Gail’s nose wrinkled. An hour? A day? She scowled at the downpour. Shadows were meant to stay stuck, like ears and promises. They weren’t meant to run away. They were especially not meant to run away when it was raining. Or on your birthday.

Gail’s stomach twisted as she heard the bed creak upstairs. Kay’s shadow hadn’t just run away. It was Gail’s fault. If she hadn’t kicked it… The hurt in Kay’s brown eyes bubbled in front of her. “I chased her shadow away,” Gail said to the empty kitchen. She grabbed a photo of Kay from the fridge, stuffing it into her bag. “And now I’ll get it back.”

When she opened the door, the wind tugged at her hair. Gail squeezed her eyes against the rain, peering forward. Behind her house, the ground rose steeply towards Ben Fiadhaich, the wild hill. There it was: she could just make out the dark blur of Kay’s shadow pouring over the damp grass at the end of their garden. Gail saw it flow over the wall towards the river, which tumbled icy-cold and fierce down the hillside. “Wait,” she cried out, but the word was tugged from her lips by the wind and undone.

Rain soaked through her leggings as she ran down the garden and clambered over the wall. Here, a footpath curled along the river and out of the village for a mile, before forking into two: one beginning long-legged zigzags up the hillside, the other dipping to wind along the jagged cliff edge towards the south of the island. The shadow was metres in front of her, its shape shifting and swirling as it rolled over pebbles and through puddles.

Gail’s legs burned as she tried to keep up, blinking rain out of her eyes. At least now she was out of the house she could breathe again. Her head didn’t feel so squashed. And once she brought Kay’s shadow home, maybe everything would go back to how it was before. Before their dad walked out. Before Kay got sick. Before she stopped swimming.

Gail swallowed.

It had to.

She was out of the village now. Ben Fiadhaich loomed on her left, its slope scattered with straggles of trees and ledges of rock where shallow caves pitted the hillside like eyes. Gail crossed her fingers, hoping that Kay’s shadow would turn right towards the cliffs where kittiwakes wheeled and cried. But the dark shape slipped left at the fork, and Gail groaned and pressed her hands against her legs to push against the rise. No one climbed this side of Ben Fiadhaich. The slope was jagged and crumbling and there were too many whispered stories about the caves. Lynx Cave, Oyster Cave, Cave of Thieves.

The shadow slid in and out of her sight, slippery as a fish. It was moving further away. Now it left the path, darting over rocks and between tall pines. Gail plunged through the grass, hands lurching to steady herself against the uneven ground. As she slalomed between trees, the rain petered to a fine drizzle. Here, the ground felt alive with shadows, stretching and reaching towards her. Which one was Kay’s? How would she know? But as she saw a dark shape sweeping over the grass, her mouth twitched in relief. Of course she’d know Kay’s shadow. It was like recognising her sister’s handwriting, or hearing the sound of her footsteps on the stairs.

Gail fought to make her legs move faster but the shadow was always ahead of her. Her chest heaving in waves, she tried to sprint but a stitch pierced her side and she folded over, clutching her stomach. “I can’t,” she gasped, and she crumpled to the ground. And she lay, panting for breath, her legs stuck out in front of her, as the shadow moved steadily up the hillside, closer and closer to the caves.

Gail had short legs, big feet and seal-dark eyes that were fond of staring. Her brown cheeks were dotted with so many freckles it looked like a bowl of Coco Pops had been tipped onto them. Beneath her coat and jumper, she wore a tawny-orange T-shirt which almost reached her knees, and her sodden leggings were zigzagged blue and green. When she talked, her whole face moved, and when she ran she jumped high in the air so as not to trip over her feet. But she tried not to run if she could help it. She was a swimmer, not a runner. Gail winced. And not much of a swimmer either, without Kay.

Gail was higher and further from the village than she’d thought. Below, the island rolled down from Ben Fiadhaich, speckled with villages and towns and silver beaches. She could see the harbour to her right, reaching out towards the mainland, where her mum worked at the hospital. Fishing boats and ferries dotted the sea. Fiorport, the harbour town, was where Gail went to her new high school. She’d been looking forward to starting for months, looking forward to Kay showing her around. But then Kay hadn’t started back after summer and Gail caught the bus alone each morning, her mouth a thin silent line. Her friends had tried to understand, for a bit. But now they’d given up. Even Rin had stopped sitting next to her at lunch.

“You don’t seem like you any more,” she’d said. “You’ve changed, Gail.”

Gail grimaced. She had changed. Just like Kay had. It began when they stopped swimming together. Her edges felt wobbly and uncertain. No wonder her shadow had run away.

As a bubble of anger grew inside her, the stitch in Gail’s side prickled and she pushed her hands against it, below her ribs. It felt like a pufferfish. The spikes made her fists tighten and a flood of scarlet blotched her throat and ears. Gail took a deep breath. It had been two weeks after their dad left that she’d first felt the pufferfish inside her stomach.

On that evening, when the light had already begun to seep from her sister’s eyes, she’d found a crab shell speckle

d like a starry night sky and had taken it to show Kay. It was beautiful, covered in hundreds of tiny galaxies, and inside it was the purple of blackberry stains and twilight. Kay wouldn’t even look at it, her back curved against Gail, eyes half-closed. So Gail had pressed it into Kay’s hand, but she’d pressed too hard and the shell had crumbled like dust between their fingers. Kay had turned around then, flicking at the broken pieces of shell on her duvet, her eyes cold. She’d said that real marine biologists didn’t break stuff.

It was then that Gail had first felt a sharp blossom of spikes in her stomach and a flare of anger that made her crush the last of the starry shell in her own fist. Since then, the pufferfish inside her stomach kept her awake at night. Anger bubbled through her all the time and she couldn’t make it stop.

Gail took a deep gulp of air. Kay would make it stop. Once Gail got her shadow back, everything would return to normal.

From where she sat, halfway up Ben Fiadhaich, Gail could just make out the dip of the beach where she’d found the crab shell. There, the rock pools swam with anemones, sea urchins and snails. She could see the path that they’d fly down most days, all the way to the water. Before school, after school, weekends. Birthdays.

Some mornings the ocean was almost too blue to believe in. Other days, they darted from the grey rush of it, daring each other to stand further and further out on the rocks so that they came home soaked and shivering, the dare shining out of their eyes. Kay always went further than Gail. Always two steps closer to the edge.

The drizzle had stopped. Gail bit her lip and lurched to her feet, turning away from her home towards the south of the island. Here, the ground rose knuckled and gnarled. Around the dark tangle of Grimloch Woods, hills towered, threatening as shark fins, their sides tumbling down into steep valleys and lochs where the cold, luminous water seemed to reflect skies from whole other worlds. It was a long and treacherous hike to reach the sharp southern tip of the island, where the ocean lashed at the cliffs and the path crumbled into jagged arches. Few people walked that way, and even fewer lived there.

The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow

The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow